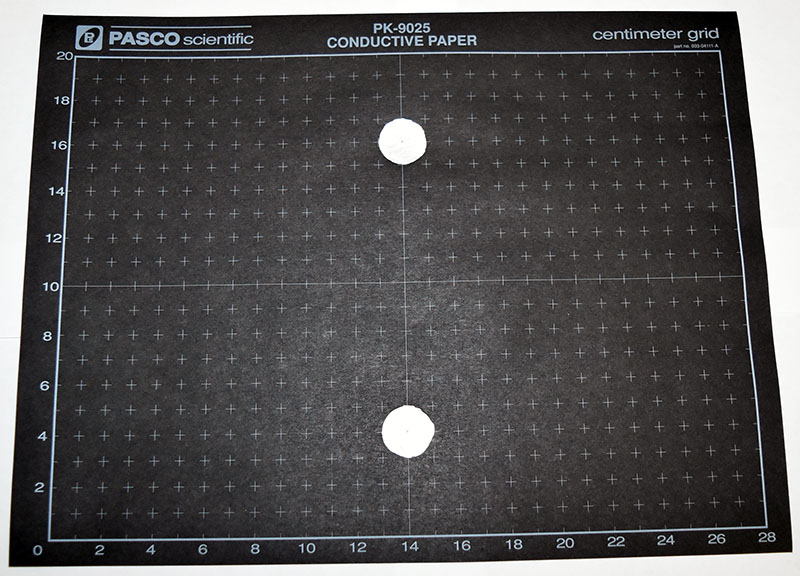

Model 1 Resistance between two disks on the infinite conducting plane.

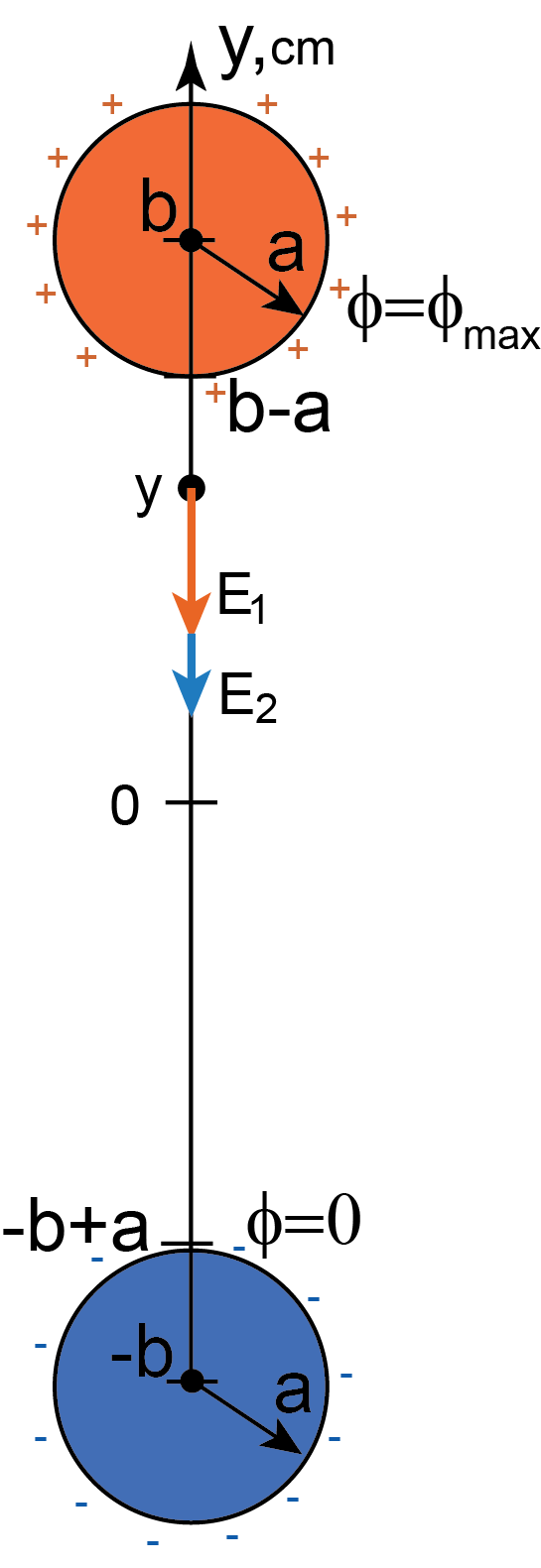

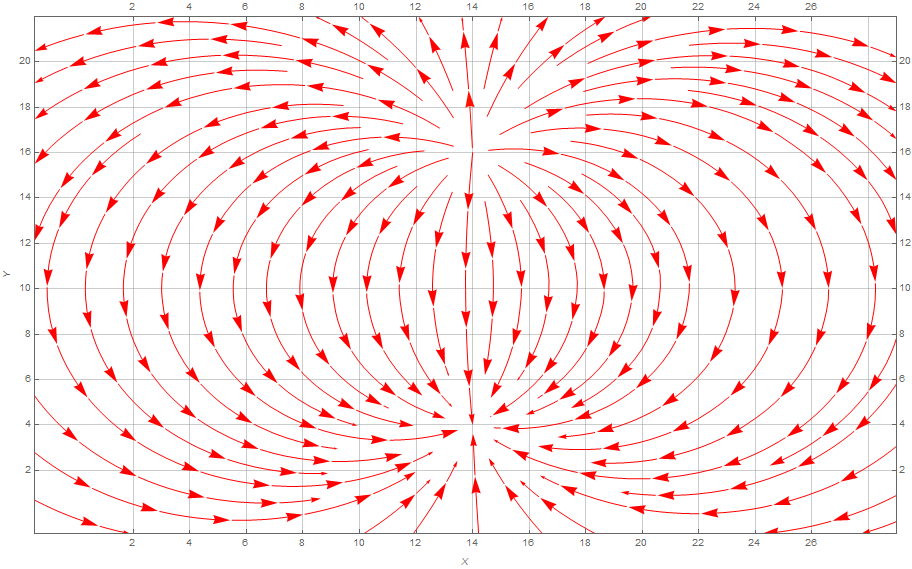

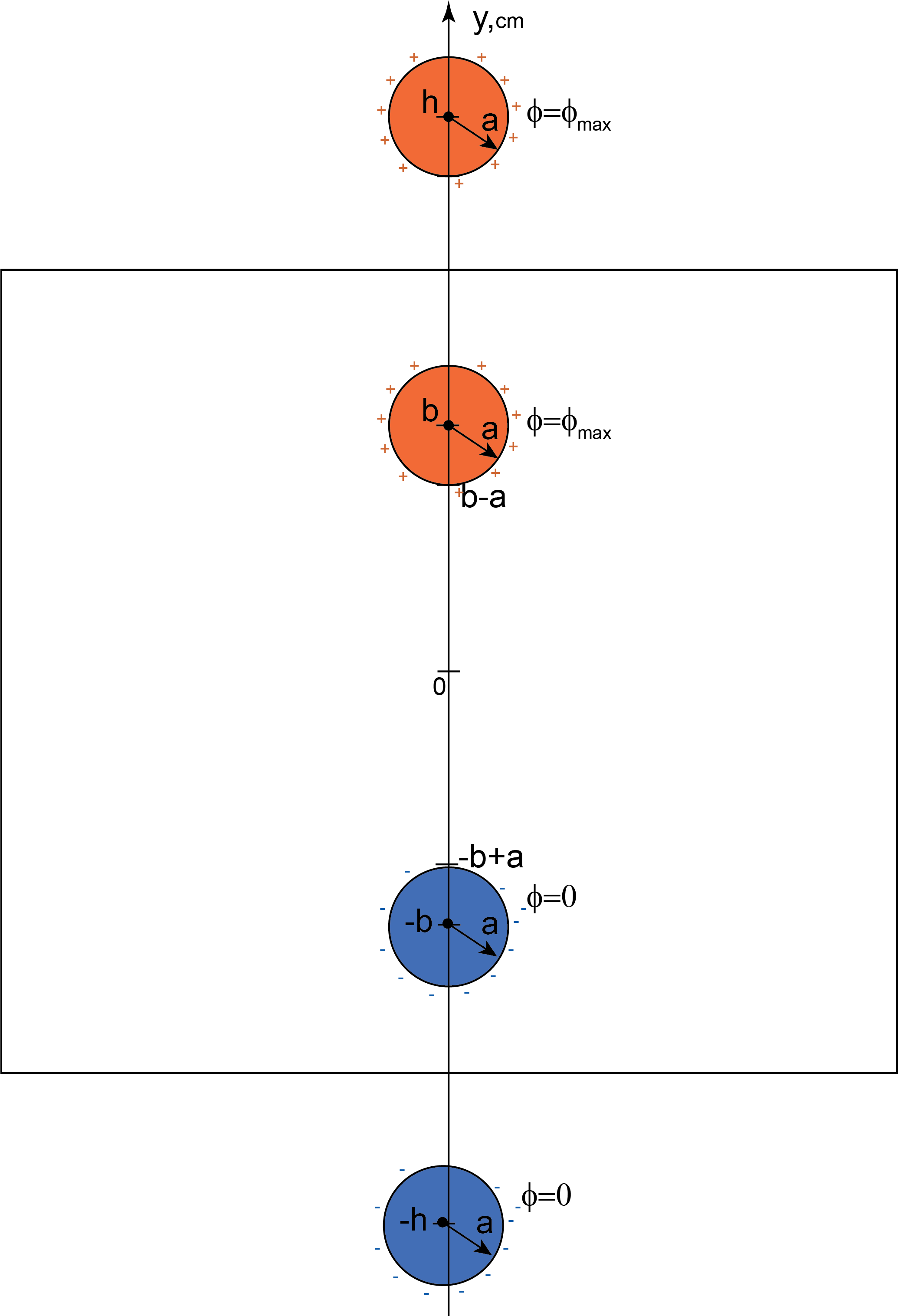

We consider electric field by two identical oppositely charged very thin disks on the plane (see Figure M.2). The charges on these circles are produced by connecting them to the voltage source that maintains known potential difference ![]() between them. This is a “2D” case – electric field lies in the plane of the disks. You may think of these disks as cross-sections of very long charged cylinders (due to translational symmetry electric field lies in the plane perpendicular to the axes of the cylinders).

between them. This is a “2D” case – electric field lies in the plane of the disks. You may think of these disks as cross-sections of very long charged cylinders (due to translational symmetry electric field lies in the plane perpendicular to the axes of the cylinders).

- Recall that in “2D” case the magnitude of the electric field due to charged disk is inversely proportional to the distance from its center:

- Let us determine the value of the constant

. Assume the disks have radii

. Assume the disks have radii  and their centers lie on

and their centers lie on  axis at points

axis at points  and

and  . Consider electric field at some point on the

. Consider electric field at some point on the  axis between the circles(see Figure M.2). We assume the “upper” circle is at potential

axis between the circles(see Figure M.2). We assume the “upper” circle is at potential  while the “lower” circle is at 0 potential (connected to GND). Electric field at point

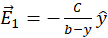

while the “lower” circle is at 0 potential (connected to GND). Electric field at point  due to “upper” positively charged disk is

due to “upper” positively charged disk is  . Electric field at point

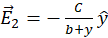

. Electric field at point  due to “lower” negatively charged disk is

due to “lower” negatively charged disk is  . Electric fields

. Electric fields  and

and  have the same direction therefore the net field at point

have the same direction therefore the net field at point  is:

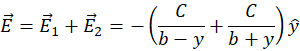

is:

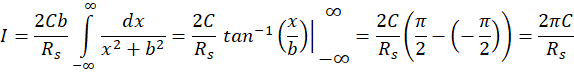

(M.2)

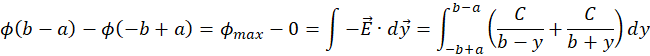

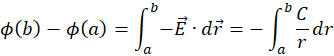

The difference in electric potential between the disks:

(M.3)

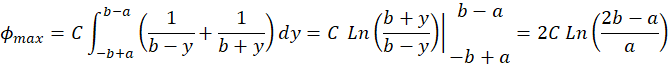

Integrate (M.3):

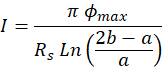

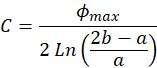

Express

in terms of

in terms of  ,

,  ,

,  :

:

(M.4)

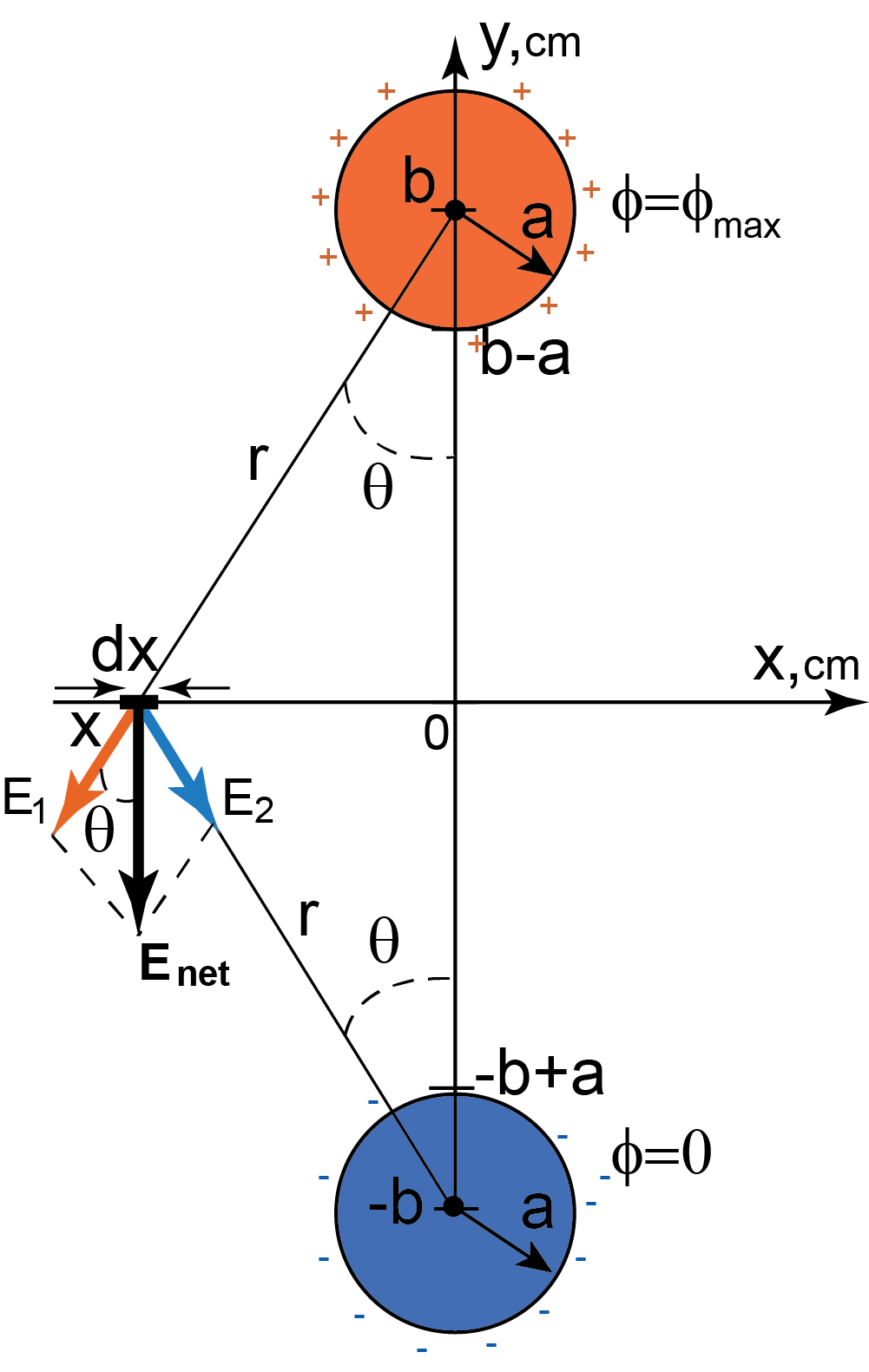

You derived this result in Prelab assignment for Lab 2. - Now consider a point on

axis (see Figure M.3).

axis (see Figure M.3).  axis is a symmetry line in our setup. Electric fields

axis is a symmetry line in our setup. Electric fields  and

and  at this point due to “upper” and “lower” circles add up to the net field

at this point due to “upper” and “lower” circles add up to the net field  that has only

that has only  component (due to symmetry). The magnitude of

component (due to symmetry). The magnitude of  :

: - The current through the small segment

is perpendicular to the

is perpendicular to the  axis and has the magnitude (see (I.6)):

axis and has the magnitude (see (I.6)): - Integrate (M.6) to obtain the net current crossing

axis:

axis:

Plug in our expression for from (M.4):

from (M.4): - Comparing (M.7) with Ohm’s Law

we obtain expression for the resistance between two thin disks on the infinite conducting plane:

we obtain expression for the resistance between two thin disks on the infinite conducting plane: - There is alternative (and shorter!) way to derive (M.8). Consider a circle of radius

- i.e. a circle that contains one of our disks (positive, for example). The current flows radially outward through this circle. Therefore, the net current through the circle is (see (I.5))

- i.e. a circle that contains one of our disks (positive, for example). The current flows radially outward through this circle. Therefore, the net current through the circle is (see (I.5))  where

where  (i.e. the length of the line perpendicular to

(i.e. the length of the line perpendicular to  is just a circumference of the circle of radius

is just a circumference of the circle of radius  since

since  is directed radially outward, i.e. perpendicular to the circle). Use (M.1) and (M.4) to express the magnitude of

is directed radially outward, i.e. perpendicular to the circle). Use (M.1) and (M.4) to express the magnitude of  at distance

at distance  from the center of the circle and obtain expression for the current in terms of

from the center of the circle and obtain expression for the current in terms of  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  . Compare resulting expression for current with Ohm’s Law (as was done in part 6) and obtain expression for the resistance between two thin disks on the infinite conducting plane (M.8).

. Compare resulting expression for current with Ohm’s Law (as was done in part 6) and obtain expression for the resistance between two thin disks on the infinite conducting plane (M.8).

|

(M.1) |

|

(M.5) |

|

(M.6) |

|

(M.7) |

|

(M.8) |

What to submit in Prelab:

Your alternative derivation (from part 7) for the resistance between two thin disks on the infinite conducting plane (M.8).

Note

Electric field line crossing the boindary means, according to the Ohm’s law ![]() that some current leaves the sheet, which cannot happen.

that some current leaves the sheet, which cannot happen.

Another way to think about it – electric field lines crossing the boundary would violate the Gauss’s Law – if we draw a small closed surface around the boundary we end up with nonzero flux of electric field through that surface although there is no charge enclosed by such surface.

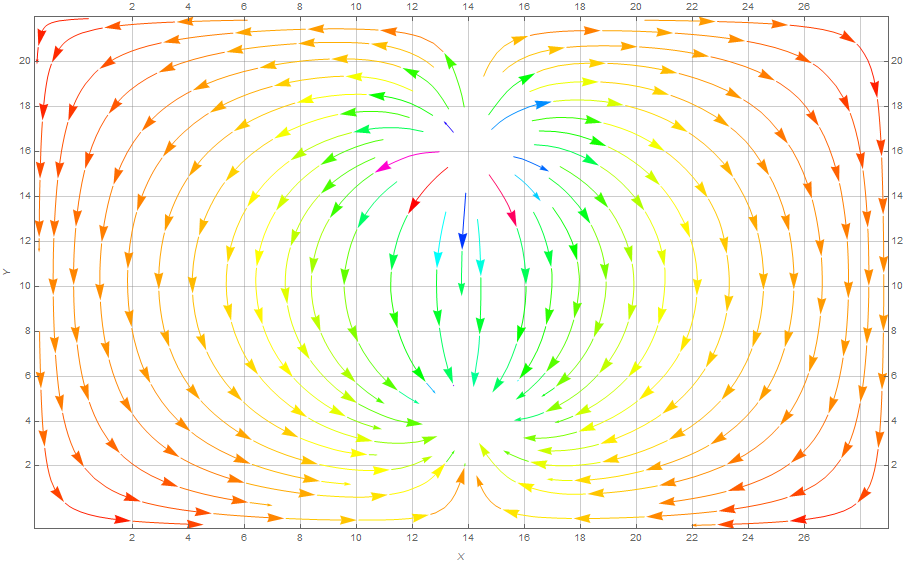

Current model does not consider the finiteness of the sheet and allows electric field lines to cross the boundary (see Figure M.5). This leads to some inaccuracy in its estimates for potential, electric field, current and resistance.

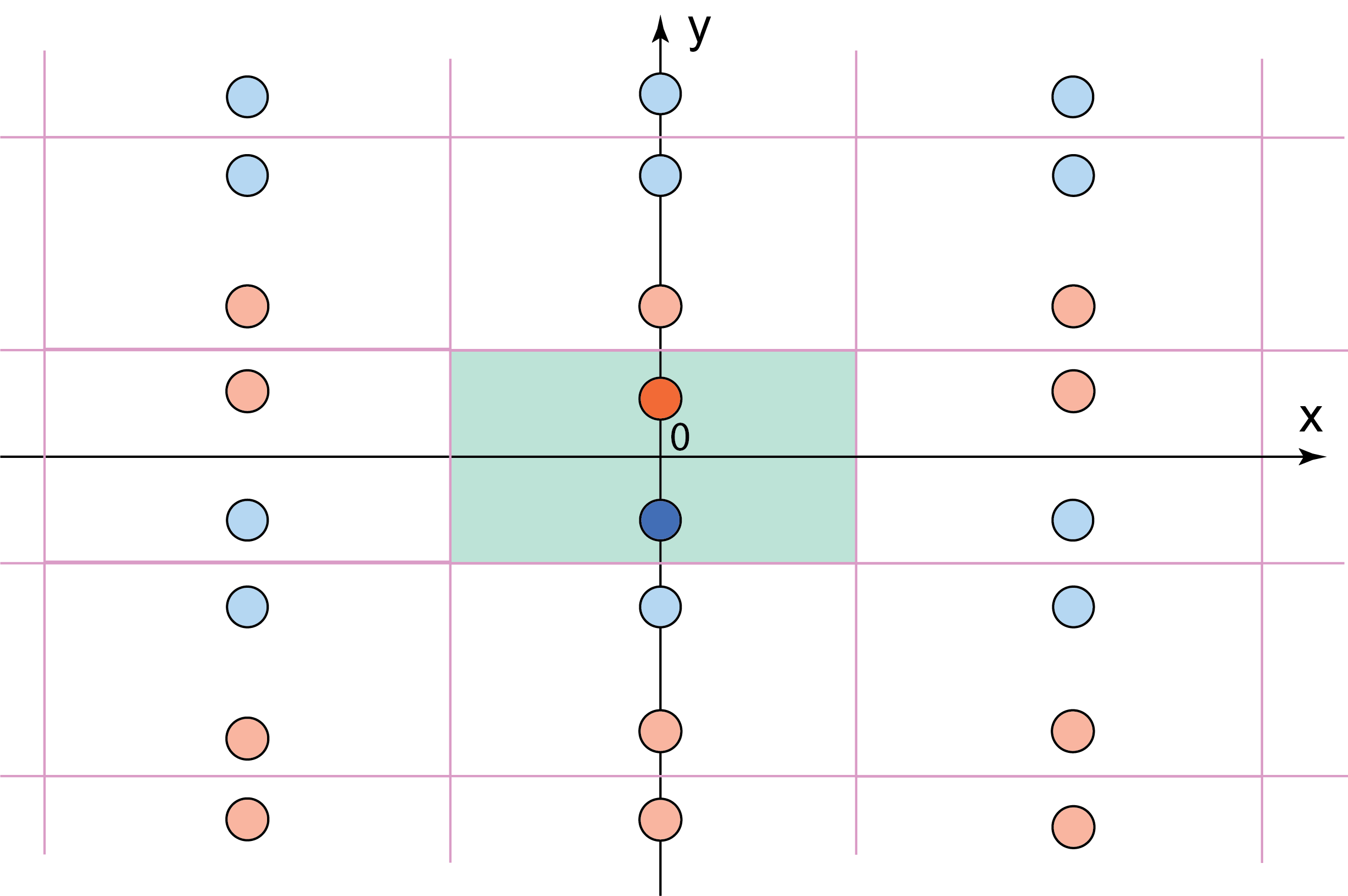

How can we adjust this Model to treat boundaries correctly? We may introduce images charges (see Figure M.6). Consider the upper boundary of the paper. Positive circle is located close to that boundary. We may place identical positive image circle above the boundary, so that both the positive circle and its image are symmetric with respect to the upper boundary. Electric field created by the positive circle and its image is parallel to the upper boundary everywhere at that boundary.

As we consider images located further away from our sheet their contributions to the electric field and the current decrease with their distance to the sheet. Therefore, as a good first approximation, we may consider only electric fields by the circles themselves and their nearest images (shown in Figure M.6). Calculations of the equivalent resistance of the finite sheet that take into account charged disks and their nearest images are very similar to our deviation in Model 1. You will not need to perform these calculations in this lab.

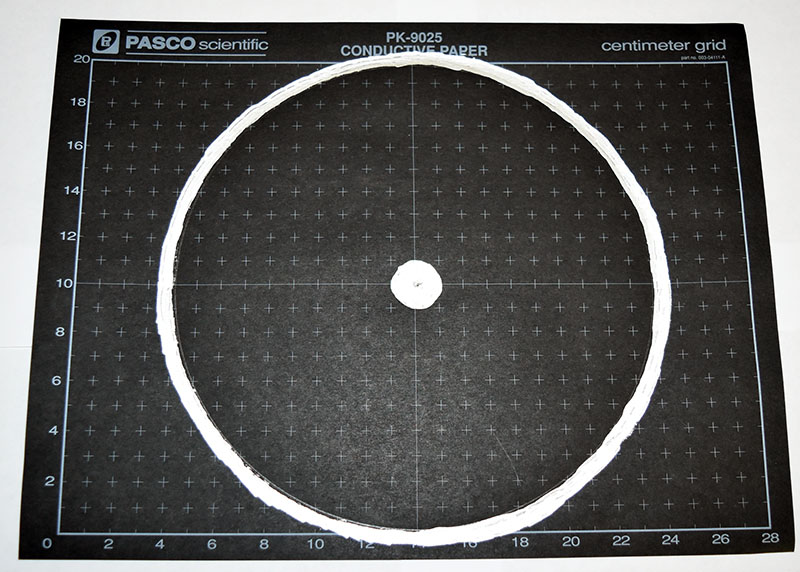

Model 2 Resistance between two concentric circles.

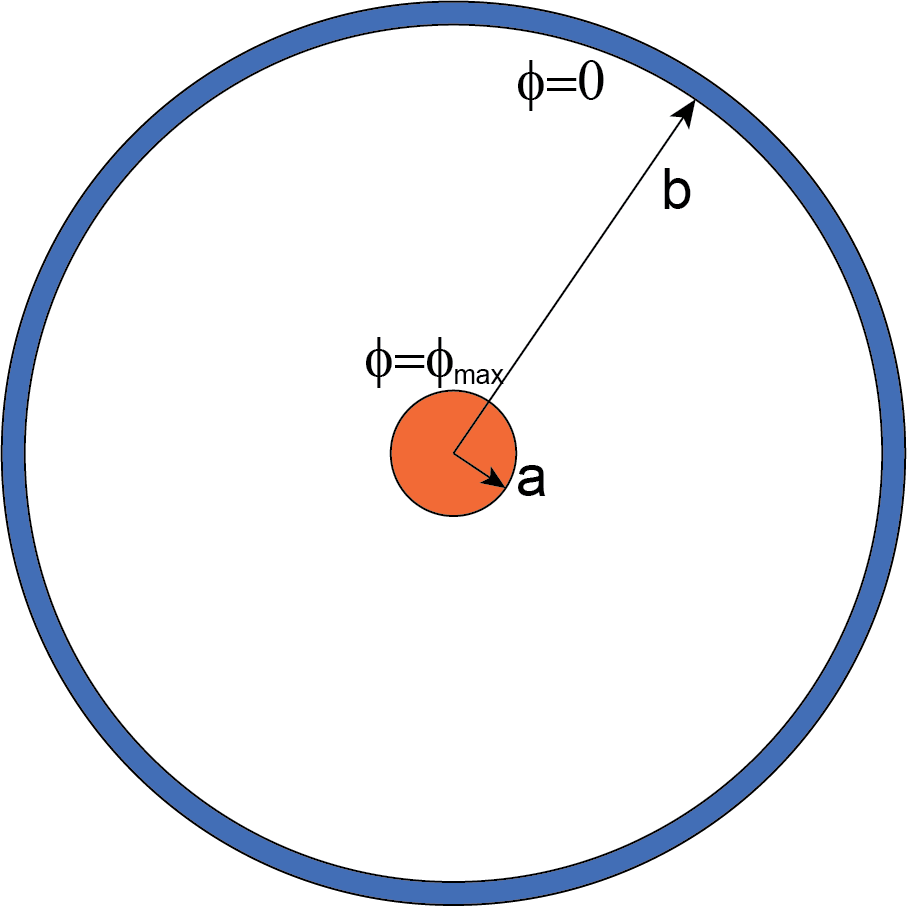

Assume the radius of the small circle is ![]() and the radius of the large circle is

and the radius of the large circle is ![]() . We will assume (as in Lab 2) that the small circle is at potential

. We will assume (as in Lab 2) that the small circle is at potential ![]() while the large circle is at potential 0 (see Figure M.9).

while the large circle is at potential 0 (see Figure M.9).

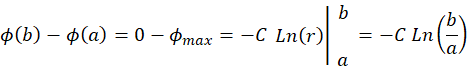

- Electric field in this setup is directed radially outward and, due to circular symmetry, is inversely proportional to the distance from the center:

(M.9)

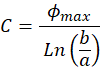

- We need to find coefficient

and express it in terms of

and express it in terms of  ,

,  , and

, and . Express the difference in electric potential between the circles through the line integral of electric field along the radial line:

. Express the difference in electric potential between the circles through the line integral of electric field along the radial line:

(M.10)

Integrate (M.10):

Express

in terms of

in terms of  ,

,  ,

, :

:

(M.11)

You derived this result in Prelab assignment for Lab 2.

- Use (M.9) and (M.11) to express the magnitude of the electric field at distance

from the center in terms of

from the center in terms of  , a, b.

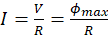

, a, b. - Now let us take a circle of arbitrary radius r:

. The current flows radially outward through this circle. Therefore the net current

. The current flows radially outward through this circle. Therefore the net current  through the circle may be calculated taking

through the circle may be calculated taking  (i.e. the length of the line perpendicular to the

(i.e. the length of the line perpendicular to the  is just a circumference of the circle of radius

is just a circumference of the circle of radius  since

since  is directed outward, i.e. perpendicular to the circle). Obtain expression for the current in terms of

is directed outward, i.e. perpendicular to the circle). Obtain expression for the current in terms of  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

. - Compare your expression for the current with Ohm’s Law

and obtain the expression for the resistance

and obtain the expression for the resistance between the circles in terms of

between the circles in terms of  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

What to submit in Prelab:

- Your expression for the resistance

between the circles with a short derivation.

between the circles with a short derivation. - Does this model suffer from the same failure to account for the finiteness of the sheet as Model 1? Do we need to introduce image charges in this model to ensure correct behavior of electric field at the boundaries?

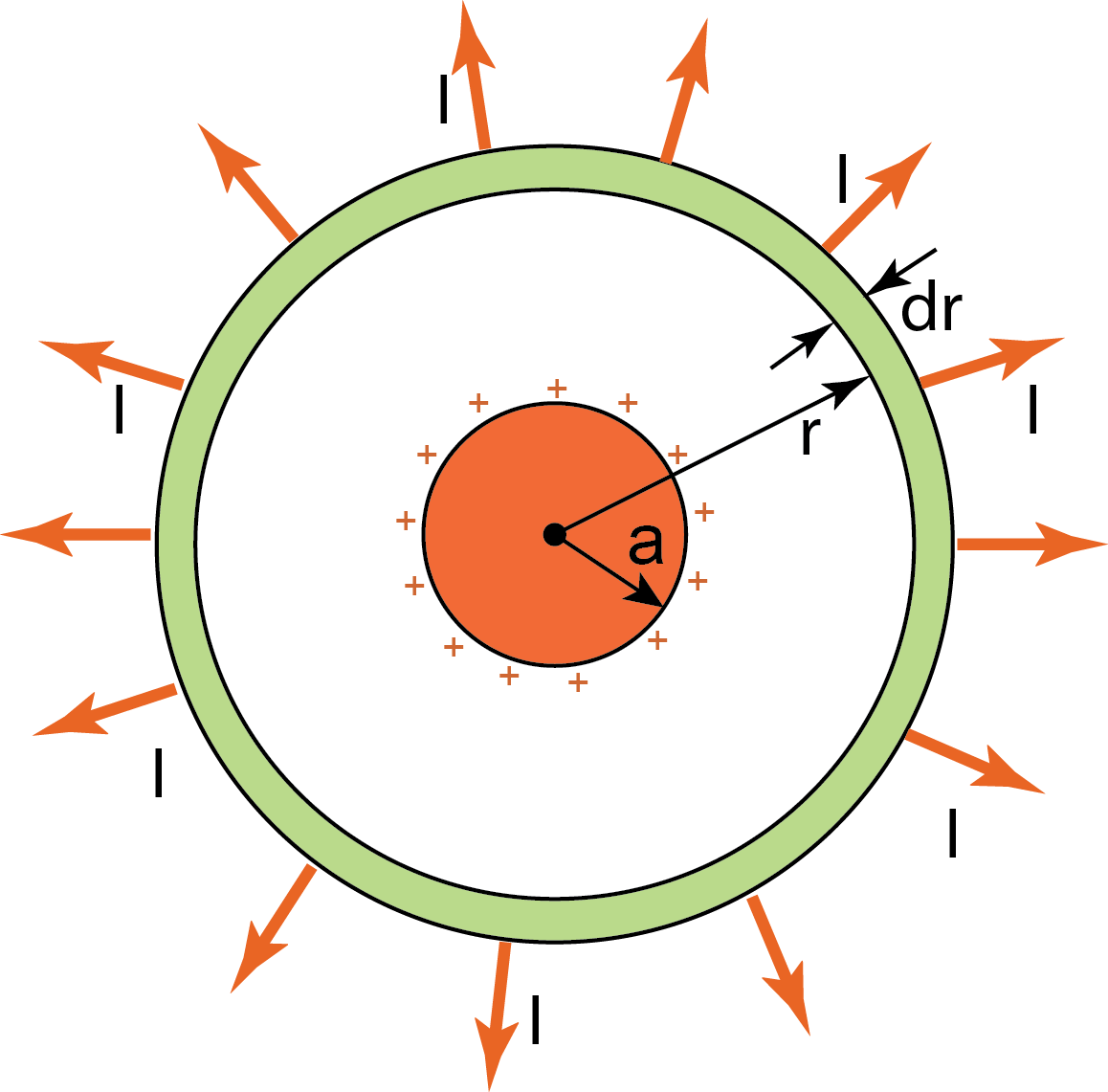

Alternative derivation.

![]() and thickness

and thickness ![]() (Figure M.10). The current through the ring flows radially outward. Therefore, the resistance of this ring is

(Figure M.10). The current through the ring flows radially outward. Therefore, the resistance of this ring is

![]()

Here the ![]() is the "length" of the conductor (i.e. the extent of the conductor in the direction of the current),

is the "length" of the conductor (i.e. the extent of the conductor in the direction of the current), ![]() is the "width" of the conductor. It is the circumference of the ring:

is the "width" of the conductor. It is the circumference of the ring: ![]() (i.e. the extent of the conductor in the direction perpendicular to the current). Therefore:

(i.e. the extent of the conductor in the direction perpendicular to the current). Therefore:

![]()

We can subdivide the area in between our concentric circles on many such thin rings. These rings will all be "connected in series" as the current flows directly from one ring to the next. Therefore, the net resistance between our concentric circles of radii ![]() and

and ![]() is the sum, i.e. the integral of such

is the sum, i.e. the integral of such ![]() s. Integrate to obtain the net resistance. Compare with your expression for this resistance you obtained earlier.

s. Integrate to obtain the net resistance. Compare with your expression for this resistance you obtained earlier.

What to submit in Prelab:

- Your alternative derivation for the resistance between the concentric circles and your answers on the questions above.

- Not mandatory (extra credit). Can you always use the approach we used in the alternative derivation for this model – i.e. subdivide the object on many thin layers, find resistance of each thin layer and then add it up (integrate) to obtain the net resistance of the object? If not, under what circumstance can we use this approach? You might want to check homework problems 4.6 and 4.32 before you answer this.